My Journey to RG: Introducing Virginia

Hi, my name is Virginia Weihs. I live in Seattle, where I have been active in praxis groups and the RG Seattle chapter leadership team for the last two years, and I recently started a position as a POC (People of Color) Organizing Fellow with RG. I am 28 years old, mixed race — Chinese-American and white — and grew up in a wealthy family. This blog post shares a little more about my own journey to RG, and the tools, perspective, and power that joining RG has given to me.

Before having the powerful lens of class to understand my own experience, having privilege felt both like a hugely formative part of my life, and also like something that was very difficult to wrap my mind around. Growing up in a loving family with two doctor parents, I never had any doubts about being able to get my needs met, and the opportunities I had for education, exploration, and self-discovery felt practically endless. A lot of the time, I took these things for granted, but sometimes, my own good fortune was thrown into sharp relief. Even in the world of wealthy neighborhoods and private school I was a part of, where it would seem easy to avoid the understanding that people lived any other way, there were truths about the exclusivity and privilege of our lives that could never stay fully concealed. For me, I think these truths came up most powerfully in the subtle, small moments — the awkward conversation about which brands of jeans our families bought with one of my few classmates whose family wasn’t wealthy; the tension on our private school bus rides home between the bus driver who refused to indulge the antics of students, and the students who loved to heckle him anyway; the brief interactions with the domestic workers who cleaned my family’s home and the homes of my friends — a normal part of the background of our busy lives.

In the predominantly white environments in which these moments took place, class differences were often accompanied by racial difference. Sometimes, the ways these differences came hand in hand felt incredibly stark. It wasn’t always so clear cut though. While the racial wealth divide was alive and well, it wasn’t only the white people who had wealth and privilege, nor was it only the black and brown people who were struggling or in a position of service. As I considered my own race/class position, the potent combination of the model minority myth and my lack of exposure to racially and economically diverse spaces brought me to the conclusion that all Asian people were rich. This deeply felt but very skewed theory demonstrated the lack of avenues I had available to me for fuller understandings of race and class, even as I experienced race and class dynamics in play all around me.

My political education began in college. It was there that I started to learn powerful new analytical frameworks to understand the world. These frameworks used language like “power” “institutionalized”,“oppression”, “privilege”, “equity”, and “liberation” and talked about the socially constructed nature of systems like race and gender. I felt transformed by these new ways of thinking, like a curtain had been pulled back to reveal how the forces that stratified people were not natural, but rather, had been deliberately designed and forcibly implemented to maintain the power of certain groups of people over others. This experience catalyzed a strong desire within me to participate in creating a more just world. And yet, the role of class remained importantly left out of much of this examination.

Echoing my experience in high school and earlier, one of the most significant impacts of not having the tools to name class, or to distinguish the ways that class privilege had so importantly shaped my life, was the way it affected how I understood my racial identity. In college, a large part of the politicization process for many people was a bold claiming and investigation of their own identities. Asserting an identity as a person of color was a way that many people named their lived experiences of racial oppression and resilience. But the circumstances in which I had grown up made it feel disingenuous in many ways for me to claim those experiences. I felt that that I had not been and never could be vulnerable to the disenfranchisement and disregard that racism had brought to the lives of other people of color. I wondered if the discrepancies I perceived were because I was half white, or third generation, or East Asian. Sometimes I just tried to ignore my feelings, but without fail, they’d come back to provoke and haunt me, fostering in me a sense that my racial identity would remain an unresolved and raw question.

Joining RG and moving towards claiming a privileged class identity felt like a scary step to take — it made me wonder if I was risking putting even greater distance between me and communities of color with whom I deeply desired to be in relationship and solidarity, and to whom I also have often felt disconnected. But, joyously, what I have found instead is that bringing the truth, depth, and complexity of my full experience gives me a sense of both accountability and wholeness that I’ve been unable to feel when I’ve tried to obscure parts of my story that I was afraid did not belong. Getting to know other young people of color with access to wealth/class privilege, I have come to understand my story is not unique, and that “person of color” is an identity big enough to include experiences like ours. Furthermore, I have seen the power that comes from explicitly talking about our experiences as class privileged people of color, and the important role we have to play in the larger struggle for racial and economic justice.

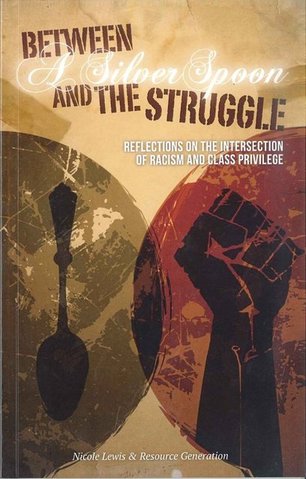

As many wise people who have come before me have taught me: people of color with wealth are uniquely positioned to contest the narrative that racism no longer exists and that anyone can make it in our society should they work hard enough. When armed with the details of our stories — the privilege and access that already existed, the lucky breaks, the many people in our communities who have not achieved the same success — we can show how our levels of wealth and access are the exceptions that prove the rule. In the ways that our stories have common patterns or themes along racial lines, we can flesh out the differences in the experiences of different groups of people of color, explore how structures of power have operated to position us differently, and expose where we’ve been pitted against each other in ways that ultimately benefit none of us. Our stories can also complicate and deepen understandings of how assimilation works — how it is so persuasively framed as success, but how it often also comes with great losses. (For more stories of young people of color with wealth, check out RG’s most recent publication, Between A Silver Spoon and the Struggle, by Nicole Lewis and RG).t by examining the intersectional impacts of class and race, among other identities, on our lives, we can work more strategically and effectively for a world that is good and bountiful for everyone. Exploring my class privilege has been an integral part of this process for me. It is not always straightforward or easy, and I have a lot further to go. But it continues to feel like work that is critically important and also liberating.

In the POC Organizing Fellowship position, I will be reaching out to people of color with wealth in Seattle and the Bay Area. Please feel free to reach out to me too — I am excited to do this work with you.

*Thank you to the wonderful Nitika for her help with writing this post!