The Responsibility of Freedom, the Freedom of Responsibility

“Freedom is what you do with what’s been done to you.” – Jean-Paul Sartre

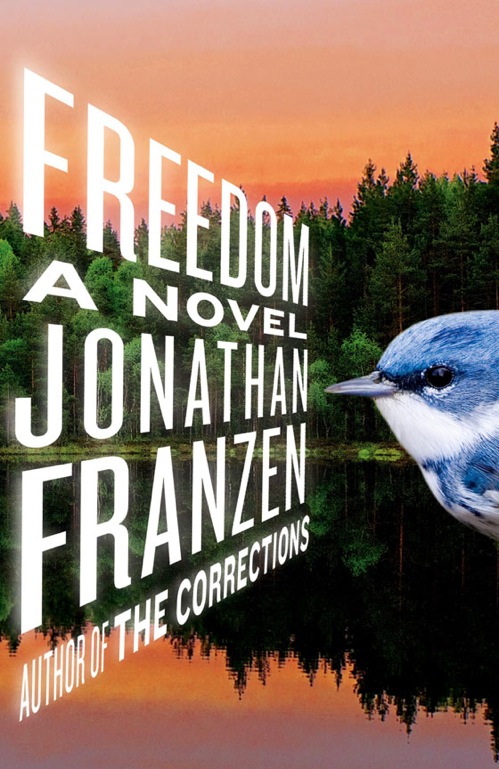

There’s a new book about freedom. It’s called Freedom. It’s not a political book. It’s a novel, written by Jonathan Franzen, who last month’s Time magazine cover proclaimed to be the “Great American Novelist.” (Who knew that there were still novels? Let alone novelists? Let alone great ones? But that’s another entry for another forum for another day…) I have not read the book – novel, sorry. Nor do I plan to. My literary ADD requires that my reading diet consist almost exclusively of nonfiction (a societal problem Franzen speaks of in the Time piece). But I did enjoy the cover article very much, finding the portion of its discussion of freedom, Freedom the idea, Freedom the ideal, Freedom the bumper-sticker phrase, to be particularly poignant for the RG community. For who has more freedom than the financially privileged? The freedom to choose what to do and what not to do, how to do it, and when. The freedom to cultivate a life of one’s own choosing.

“It seemed to me,” Franzen tells article author Lev Grossman, “that if we were going to be elevating freedom to the defining principle of what we’re about as a culture and a nation, we ought to take a careful look what freedom in practice brings.”

From Rage Against The Machine to the Tea Party to Mel Gibson’s William Wallace, the one thing we all want is freedom. Or more freedom. Or as much freedom as possible. But there’s little societal discourse on what one should do when they have that freedom.

“The weird thing about the freedom of Freedom,” Grossman notes of the characters in Franzen’s new novel, “is that what it doesn’t bring is happiness.” Ironically, freedom has its limitations. “For Franzen’s characters,” continues Grossman, “too much freedom is an empty, dangerous, entropic thing.”

Freedom can be debilitating. Resulting in a sort-of enervation that is the exact opposite of effective activism. There is an ever-present “agony of being connected to everything in the universe,” as the subtitle of Andrew Boyd’s book (not a novel, though filled with many novel ideas) Daily Afflictions suggests. To amend this slightly for the financially privileged, there is an agony of benefiting from the systemic everything in society. And this reality can be a debilitating, enervating, entropy-destined one to (attempt to) negotiate.

But does it always have to be so agony-inducing? Not according to Grossman, who suggests that “there is something beyond freedom that people need: work, love, belief in something, commitment to something.” (I could put in a pitch to become an official member of the RG community here, but I won’t.)

I’ve always been struck by the relationship between freedom and responsibility. How the more freedom one has, the more responsibility they need to use in conjunction with that freedom. And that the less freedom one has, the less responsible they are for all those areas of their life where they are not (as) free to cultivate as they might wish. (Ironically, those with the most freedom, who often use the least amount of responsibility in its cultivation, seem to talk/complain endlessly about the lack of responsibility used by those with the least amount of freedom in our society.)

So while everyone seems to want freedom, the correlative responsibility that goes along with that privilege isn’t quite as popular. This has been demonstrated several times by various societally-enhancing or detracting moments, including, not most notably, the wah-guitar inspired chorus to 1990s pop music hippie-worshipping sensation The Soup Dragon’s, hit “I’m Free”:

I’m free

To do what I want

Any old time

A nice notion, to be sure. But the unfortunate thing about one’s freedom is that it affects everyone around you. One person’s freedom is another person’s problem. And ignoring this interconnection can only get one so far. After all, “no one is freer than a person with no moral beliefs,” notes Grossman. Again, freedom has its limitations.

But, if freedom isn’t a sufficient enough route to happiness, either of the personal or societal variety, than what’s a wannabe-responsibly-privileged person to do?

Maybe we’re never truly as free as we are when we’re being responsible, or at least intentionally attempting to be responsible, with our freedoms, with our privileges. “It’s what you do with freedom,” Grossman suggests, “what you give it up for – that matters.”

A point that is reflected in Boyd’s Daily Afflictions. “Being happy requires the rarest of things: to lose yourself in a task, to squander yourself for a purpose, to surrender to love.”

Or, as John Mason Brown suggests, “The only true happiness comes from squandering ourselves for a purpose.”

This seems fairly counterintuitive. We live in a nation of hoarders, encouraged to save it for a rainy day, a societal landscape dotted with storage facilities and closet organizers. In many ways, there is nothing scarier than squandering ourselves, even if it is for a purpose.

But this idea of squandering seems especially pertinent for the RG community, as we work collectively (and individually) to leverage our privilege for social change, to most effectively squander ourselves for our purpose/s.

What we willingly give up our freedom for defines who we are, as individual people, as a community, and as a society.

In the end, “money and fame are mediums to be used, like paint or steel or ideas,” notes Santa Fe artist Zane Fischer.

Squander away …